My friends, Bob and Nelly, are the parents of a severely autistic child who is expected to need care for his entire life. I can only imagine the financial and emotional burden they carried, yet I have never heard either complain. I’ve known Bob since grade school. He was constantly in trouble with teachers, always in detention or getting licks from the principal because he couldn’t or wouldn’t follow rules. While not rich, Bob’s family was comfortable, getting a new car every couple of years, flying away to California for vacations, allowing Bob to pick the college of his choice without concern about cost. Bob, I believed, was destined to be one of Life’s winners. After college, he graduated from law school and married Nelly who was from a similar economic background. They waited until their early thirties to have a child, wanting to be sure they could provide all of the comforts they had enjoyed to their own children. When little Richard was born, they were ecstatic. In their opinion, life couldn’t have gotten any better. When their world fell apart two years later with the diagnosis of autism and the uncertainties that Richard faced, their faith in themselves, each other, even God, was shattered.

As might be expected, everything about their life and expected future changed. For a time, things were very, very rough. Bob’s law practice suffered, their marriage was under strain as each tried to understand the cause of their son’s autism. As the extent of Richard’s disability became apparent, worries about money intensified. Nelly, as a stay-at-home Mom, seemed to bear the worst of it, spending every day with Richard, chasing every “cure”, spending hour after hour on the latest recommended therapy. By choice, their activities outside of a few close friends and family members virtually stopped. As for Richard, he gradually improved as he grew older, but never to the point of independence or even where they could leave him unattended without worry.

Acceptance & Change

But, over the years, Bob and Nelly changed, almost imperceptibly at first but more apparent as the months went by. Instead of worrying about the future, they began to embrace the present, facing each day as it came knowing that whatever trouble, tragedy, or even triumph was temporary and would pass. They learned to look past Richard’s disability to his strengths – his constant good nature, his unfailing willingness to forgive any slight or slur, his constant joy as he listened to his favorite songs over and over. More importantly, they learned to forgive themselves and to be happy once again. Bob’s legal career never fully recovered, but neither seemed to care about the lost income and the prestige that accompanies wealth.

As I struggled with my own problems, I couldn’t help but wonder what had happened? What had they discovered that I was missing? When I finally broached the subject with Bob, he simply replied, “I learned that I couldn’t, no matter how hard I tried or how much I wanted, fix Richard’s autism. Whether it was my fault, or Nelly’s from something we inherited from our folks or consumed during our college years, of any one of a thousand reasons didn’t make any difference since I couldn’t go back and change it. The only thing that I could do was change how I felt and what I did. So I did.” He smiled. “Life is what we make of it, not what somebody else does.”

Often, there is some grain of truth in old sayings and myths. That is why they persist over time and generations. As I considered my own situation, I realized that one of the first questions I needed to answer was whether I could truly change old habits and patterns of thinking, if wanting to have a different life and future is really sufficient to make the effort successful. Perhaps the desire alone is not enough and there are factors that preclude some people from ever being satisfied with their achievements or happy.

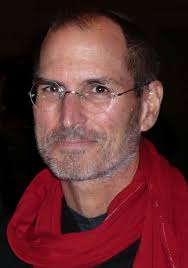

Often, there is some grain of truth in old sayings and myths. That is why they persist over time and generations. As I considered my own situation, I realized that one of the first questions I needed to answer was whether I could truly change old habits and patterns of thinking, if wanting to have a different life and future is really sufficient to make the effort successful. Perhaps the desire alone is not enough and there are factors that preclude some people from ever being satisfied with their achievements or happy. [/one_third][one_third]Who is happier – a Steve Jobs who made millions by designing products that makes life more entertaining, exciting, and easier for millions or Mother Theresa who lived a simple life while focusing the world’s attention on the poor, the homeless, the persecuted? I suspect that both were happy and both probably considered their lives a success, but neither would have changed places with the other expecting to find more happiness as a result.[/one_third] [one_third_last]

[/one_third][one_third]Who is happier – a Steve Jobs who made millions by designing products that makes life more entertaining, exciting, and easier for millions or Mother Theresa who lived a simple life while focusing the world’s attention on the poor, the homeless, the persecuted? I suspect that both were happy and both probably considered their lives a success, but neither would have changed places with the other expecting to find more happiness as a result.[/one_third] [one_third_last] [/one_third_last]

[/one_third_last]

Risk and reward are inextricably intertwined, and therefore, risk is inherent in all financial instruments. As a consequence, wise investors seek to minimize risk as much as possible without diluting the potential rewards. Warren Buffett, a recognized stock market investor, reportedly explained his investment philosophy to a group of Wharton Business School students in 2003: “I like to go for cinches. I like to shoot fish in a barrel. But I like to do it after the water has run out.”

Risk and reward are inextricably intertwined, and therefore, risk is inherent in all financial instruments. As a consequence, wise investors seek to minimize risk as much as possible without diluting the potential rewards. Warren Buffett, a recognized stock market investor, reportedly explained his investment philosophy to a group of Wharton Business School students in 2003: “I like to go for cinches. I like to shoot fish in a barrel. But I like to do it after the water has run out.”